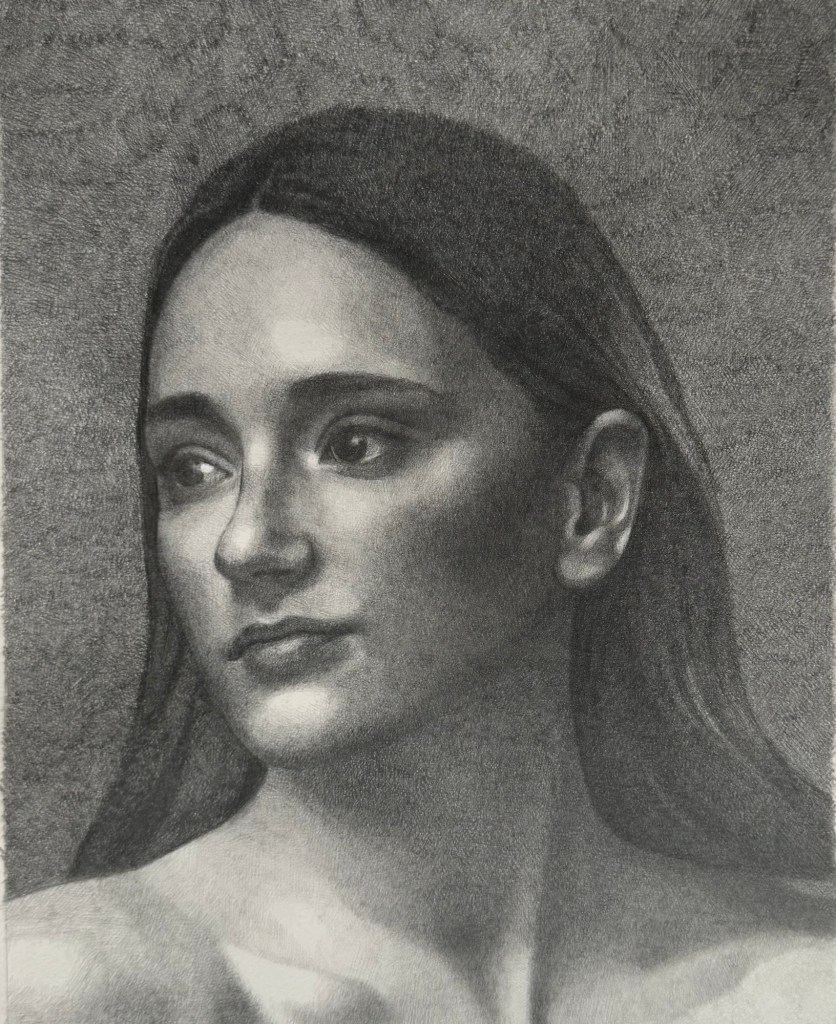

Pencil portrait

Posted on September 5, 2025

I still use the crosshatching technique I learned at school . It has an energy that reminds me of stone carving and I approach it in a similar way. Although the stone or marble carving process is different in the sense it is reductive it still has an aspect which is akin to modelling and refining with chisels.

New Pencil drawing

Posted on January 7, 2025

Creating a perfectly decorative surface

Posted on November 11, 2024

The painted surface is its own universe. I pour my life into it, gather my life on to it.

I wanted to paint in the picture a whole that shows everything at once, every thought, all time, every cause and effect. Each brushstroke is a thought that relates to all the others in one gestalt. In eastern philosophy there is the idea of Indras net, where each tie in the net has a jewel, and each jewel contains all the other jewels. Also, when we pull on one part of a net there is not a single mesh that doesn’t move. Every moment in reality contains all other moments, all time and space. Eternity doesn’t go beyond the moment. All things connect with and depend on everything else and nothing exists in isolation.

I wanted to create a perfectly decorative surface with an equal emphasis and distribution of marks throughout. To paint everything, contained in one visual present. Here everything is visible and can be grasped at once in one thought and emotion. I want to be able to sense everything at once. Everything is equally , infinitely precious. Our lives pervade the entire realm of phenomena in a single moment and so my life is contained and reflected in infinity, this infinitely profound and immeasurable beautiful space which is the subject of the painting and the painting itself. Can my life really contain everything else everywhere?

Maybe when I look at this image it sometimes gives me that impression.

Working with very small brush marks allows me to surprise myself, to see and create something in spite of myself. The image changes and surprises as I work intuitively, what I see developing on the canvas gently prompts me in new unexpected directions. Shapes emerge and lines of force are revealed to me. These surprises jolt my consciousness and allow me to see worlds I have never seen before. It is important to find something I have never seen before.

The marks may be callled dots but each one has orientation, direction. The word dot in painting conjures something mechanical, reductive, conforming. Hirst wants his dots to have this quality with the irony that they are all hand painted by his assistants.

These marks must be within similar size range, but always different, never repeating the same angle. Each one is a thought. They have a similar pressure, reach in all directions, left right up down north east south west here there to and fro, curving , squared, italicised, blotched, daubed, sweeping, halting, swelling, rounder, drier, wet, juicier, lean, fat, scratched, strong, tight, loose, good, bad, roughly equidistant. Dancing. Being steeped in the western milieu my thinking is reductive, and maybe my need for these repetitive marks reflect that. But I also want to see the whole from the outside in, like someone from the east.

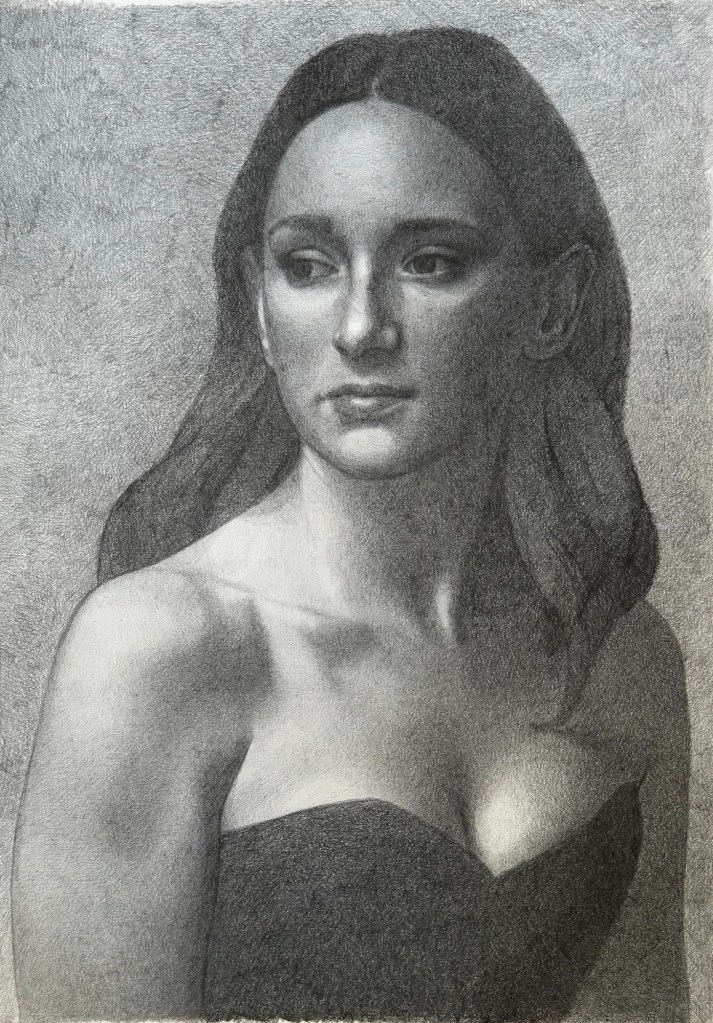

Charcoal portrait

Posted on October 9, 2024

I’m using other people’s references right now and this is from Howard Lyon. I’m very grateful that he has provided such a good resource for artists, at reasonable prices. Selecting images among the ones I bought is painstaking and it’s difficult to say exactly why I choose specific images. From 1000 images there are a handful I can use. He has created albums with choreographed themes. He says he seeks beauty in his art. This portrait is of one of his models, Katie. I’m experimenting with various media and finding out how to use charcoal. Here I am using hardest grade of Koh I Noor compressed charcoal sticks.

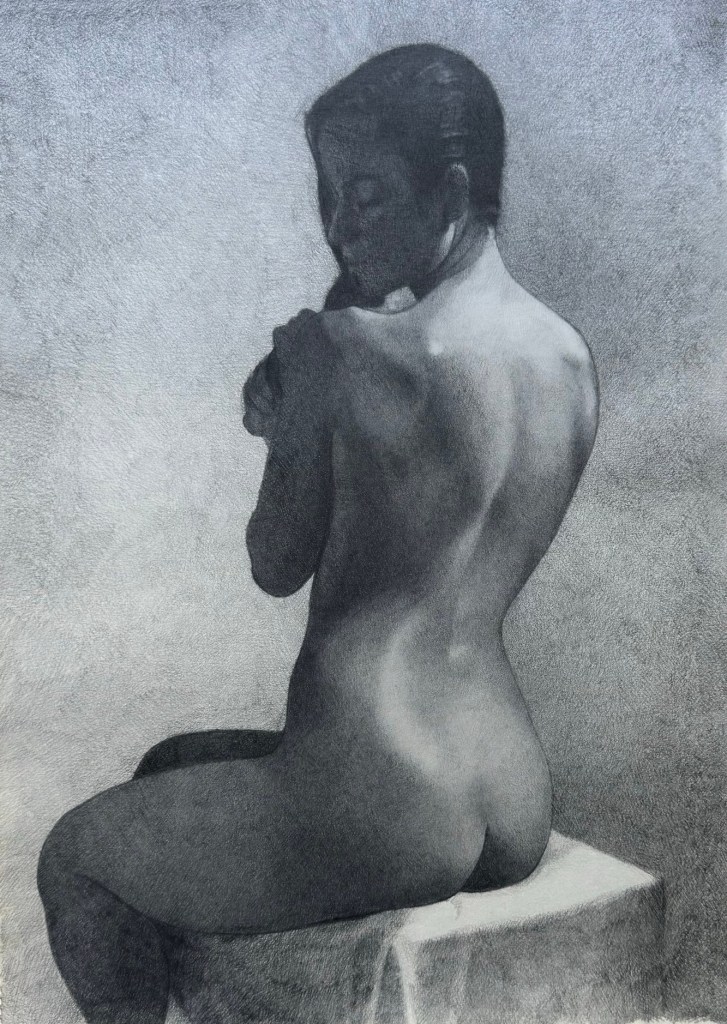

Schrödinger’s negative entropy

Posted on September 22, 2024

Schrödinger spoke about life being a kind of negative entropy and this is close to the Buddhist idea of life force that brings parts together to form a whole which is life. Buddhism says it is possible to fuse our microcosmic life with the macrocosm. And the opposite of this positive force would be entropy. Of course everything is subject to the law of entropy, everything born matures then decays and dies. But before everything turns to dust perhaps we are able to inscribe our thoughts and feelings, our lives, on canvas?

To be able to draw by gathering marks on paper must also be negative entropy, it’s a hope I can somehow create life, leave a record of my own vital life, through mark-making. Like leaving footprints which can be read by an astute observer – how fast were they travelling? How big were they? What were they thinking? Where were they going? What were their hopes, dreams? Everything is recorded there.

I become the form and rise and fall down across the musculature of the form. In an infinite and immeasurable universe our lives can also only be the same, infinite and immeasurable . And our physical lives reflect this. Hence for me the human figure is the most alluring, challenging, and beautiful thing in art.

My little finger

Posted on August 17, 2024

How can I convey the beauty of the human form? Sometimes I hold up my hand close to my eye so that I can see it out of focus and stillhouetted , and look at my little finger. A finger is a beautiful thing. I’m using mine as an example that stands for all the rest.

I’m not looking here to describe what the finger does or how it works, just what I see, what is beautiful.

Artists look, and when people look deeply at something we become aware of the miracles in reality. The specific miracle here has been created over billions of years, and the result of this development appears infinitely beautiful. It’s a finger inherent in the life of the universe itself, created by a compassionate universe.

Starting to look now at my little finger, I see there is an exquisite turn downwards from the nail, following the contour anticlockwise around the tip, which is almost a Fibonacci curve which levels into the pad of the fingerprint and then has a gorgeous sweep down to the first joint. Appearing to be a delightful straight line but still a beautifully subtle curve, this dips and rises almost imperceptibly. The fatty area is squeezed before the callus of the palm, another lovely curve echoed in the finger above. Ruskin said there isn’t a line in nature, and when drawing one should not focus on the contour. But the contour alone shows the form, an abstraction that only appears in art.

Heading the other way, past the tip, there is a wonderful pause at the nail which is just out of view from this angle. This delicately straight edge continues before rising so gently upwards to the knuckle of the first and second phalanx. The relaxed folds of the knuckle appear bumpy before rising in a fine curve of fat. Incidentally there are no muscles in fingers. As I write I am looking across a bay in Cornwall watching the undulating stone hills pitch and roll down to the sea. There are parallels here between the landscape and the body yet the landscape lacks this exquisite design. The parallel between the top and the bottom of the finger here is just slightly off and so sweet, so lovely. The musicality of these two contour lines sings.

I find it breathtaking to take in the shape of the human figure. It enthrals and captivates me. Reproducing these contours exactly as I feel them, looking deeply and carefully, is the goal of my work. There is eternity in these lines and forms. The record or journey of this looking remains on the paper like songlines. I think my way over the form and leave the drawing as evidence of this thought.

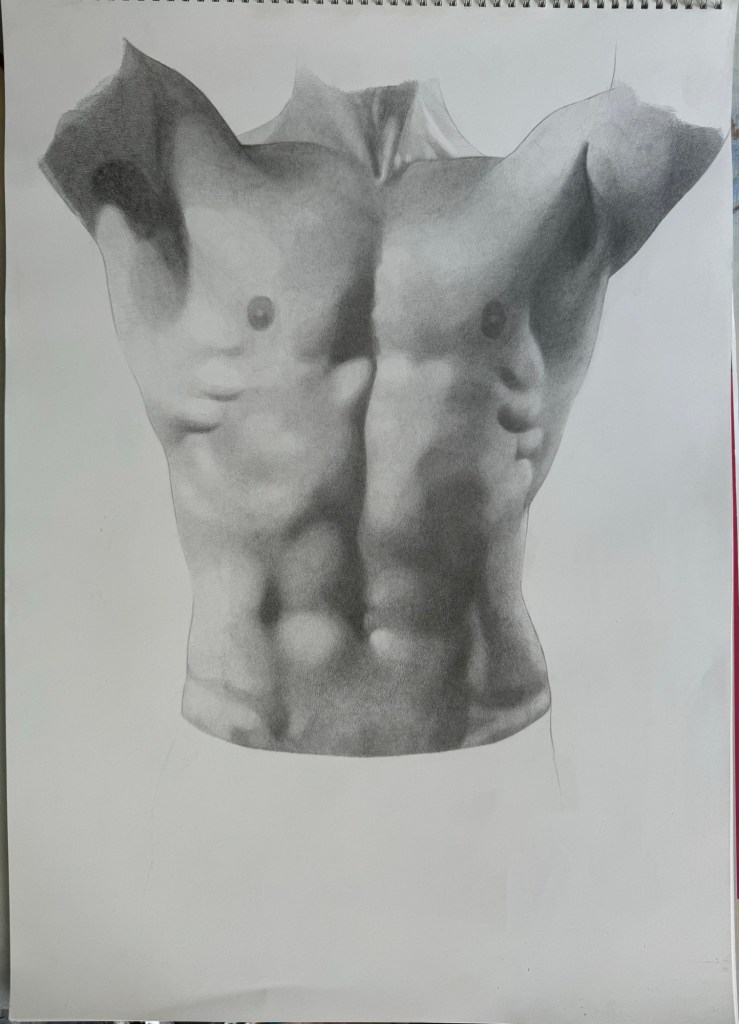

Torso

Posted on August 10, 2024

This was the first pencil drawing I have done in a while and have never worked it to such a finish. Although a closer look reveals the shading and cross hatching is still visible. The process of shading , as I’ve done here, is reminiscent of stone carving with a claw chisel. The forms are revealed by repeatedly building up layers, as if focusing a lens, refining the form. Pencil is lovely but the graphite has a shine and lack of tonal range for the darks.

When I draw a torso, I am seeking a kind of beauty, and a naked male torso is a beautiful thing. But it is not desire I feel when I study and closely scrutinise the model to draw this image. When I look at the male figures of Michelangelo I do not feel an erotic charge and yet I find in them a great beauty. When I carve a figure I rise and fall over its undulations as if in a landscape. Over and over the form, following the lines of force that bind us in space.

People talk about and reference Michelangelo’s presumed homosexuality and it may even be the case that he was homosexual, it is just not a concern that affects my reading of his work. Rather than being motivated only by male desire, the profound sensibilities displayed in his work touch deeper realms of beauty. Beauty is deeper than desire.

The slaves for example have a great power, staggering grace and facility. A beauty which then must be a truth. Why do I feel this emotion, in my heart when I look at his work, stone carved as flesh and bone. What is beauty? Keats said beauty is truth and truth beauty. I have even gone so far as to use the word ‘grace’ when looking at his drawings, when confronted with the breathtaking facility and loving tenderness he displays when drawing the figure.

But I accept that the naked human figure has an erotic aspect. Lucian Freud said that he just saw meat when he looked at a human figure. Does this mean he simply saw the human form as biological organic machine, dumb, helpless and decaying. I don’t rate Freud as much as I used to, and sometimes I find it hard to separate his destructive behaviour as a man and a father from his art. It’s a bit depressing only to see oneself and others as a decaying machine. But he also said that the simplest human gestures tell stories.

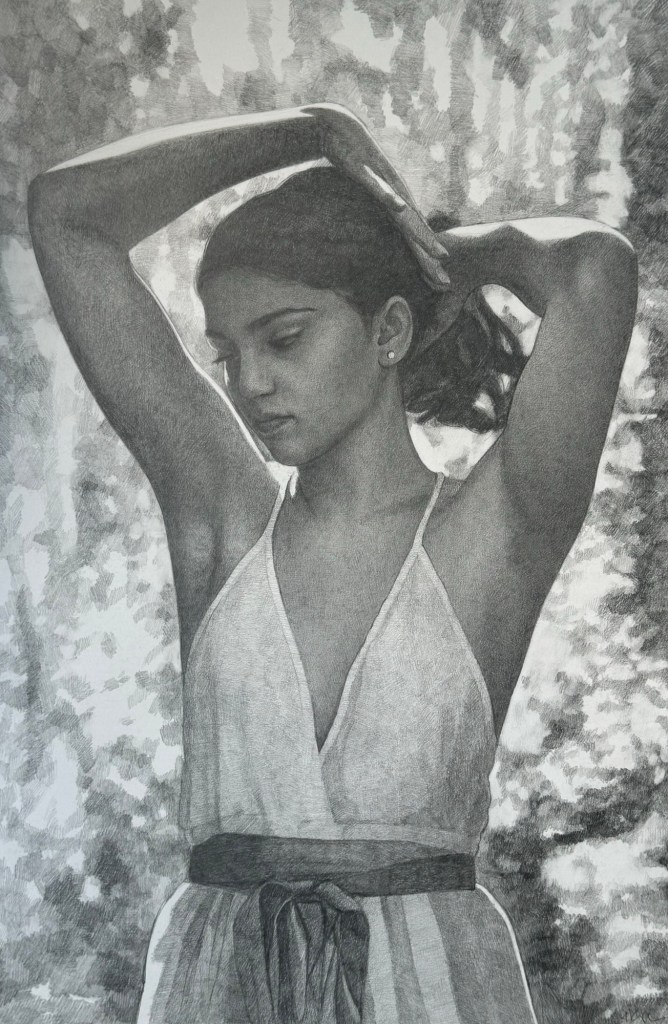

Short clip of my latest painting

Posted on May 12, 2024

I love drawing and painting the human figure. I see these paintings as sculptures though really, they are prequels to carvings.

I am wary of interpretation with these paintings. For me, in and of themselves they show the beautiful symmetry of the human form as it reflects the macrocosmic universe.

Still life with pears

Posted on November 6, 2023

Photography never does justice to painting so I would like to qualify this image by saying it’s better in real life. Since the summer I have been revisiting earlier styles of painting, ones that predate this blog..! Using mixed media with a lot of wiping out and redrawing. I didn’t think I would paint like this again, but themes that run through all my work are here – love of colour glazing, love of drawing, and modernism. It’s quite small, 20x25cm. Thanks for watching, kind regards, Matt

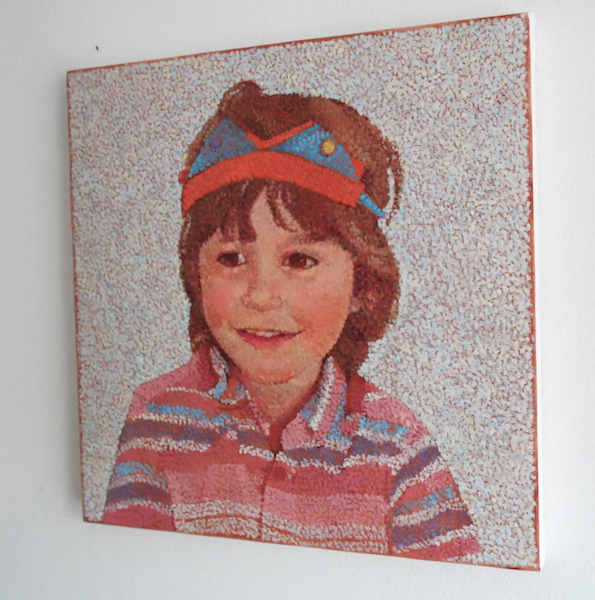

Pointillist portrait

Posted on January 17, 2022

I’m struggling to get a good image of this painting, but these should give a general idea. The one of the painting on the wall is closer to the actual colours and also gives a sense of the painting in the round. Its 30cmx30cm. I dismissed painting a portrait in this style for ages and didn’t think it would be worth trying. I have only seen very few pointillist portraits that I felt were successful. Seurat did make some of the most beautiful drawings ever made, but I wasn’t sure about the painted portraits. I’m still not completely sure about this, but after painting some landscapes using a ‘pointillist’ method I thought why not attempt it? Even with the landscapes it’s only recently that I realised it was a way of working that I could potentially stick to. This didn’t turn out to be the case as I’m restricted in terms of the amount of time I can spend on these things.

I wanted to paint a picture that was pure decoration with no hierarchy of interest or action across the entirety of the painted surface. I like the way dots animate the surface as they interact with each other but there are no greater or weaker forces. There is a great beauty and purity in the colour relations that occur, and a magic in each colour’s transformation relative to others. But I find i have to be careful as they can become visually jarring. This has to do with the ground I started working on which is a mixture of burnt sienna and umber; if its too dark the marks are set too high a contrast against it. While I talk about ‘dots’ they are really small brushstrokes, moving in different directions. If they are too uniform they look mechanical, boring, repetitive. I am conscious of moving in different directions with each stroke of the brush, but also mindful of the size of each, they need to average the same size. Some of Seurat’s paintings have a number of different size dots which I don’t think work as well. At least this is not what I am after.

I have been told off for calling myself a ‘neo’ pointillist, but really I don’t think there is any other way to describe my working method in these paintings. I am not a neo pointillist like Kusama, who is only really interested in dots for their own sake, their decoration and roundness regardless of size. or as a kind of therapy. They feel like the hallucinations of her mental illness. Strictly speaking, pointillism was about turning art and painting into a scientific method; religious paintings worshiping Science and the science of colour theory, a new science at the time Seurat was working. At its worst it fell into dogmatism in some hands. As art isn’t science and the moment pointillist paintings became dogmatic they lost some of the magic of art. I am less interested in this myself. In my paintings results are achieved by having no method. Just keep working, one brushstroke after another.

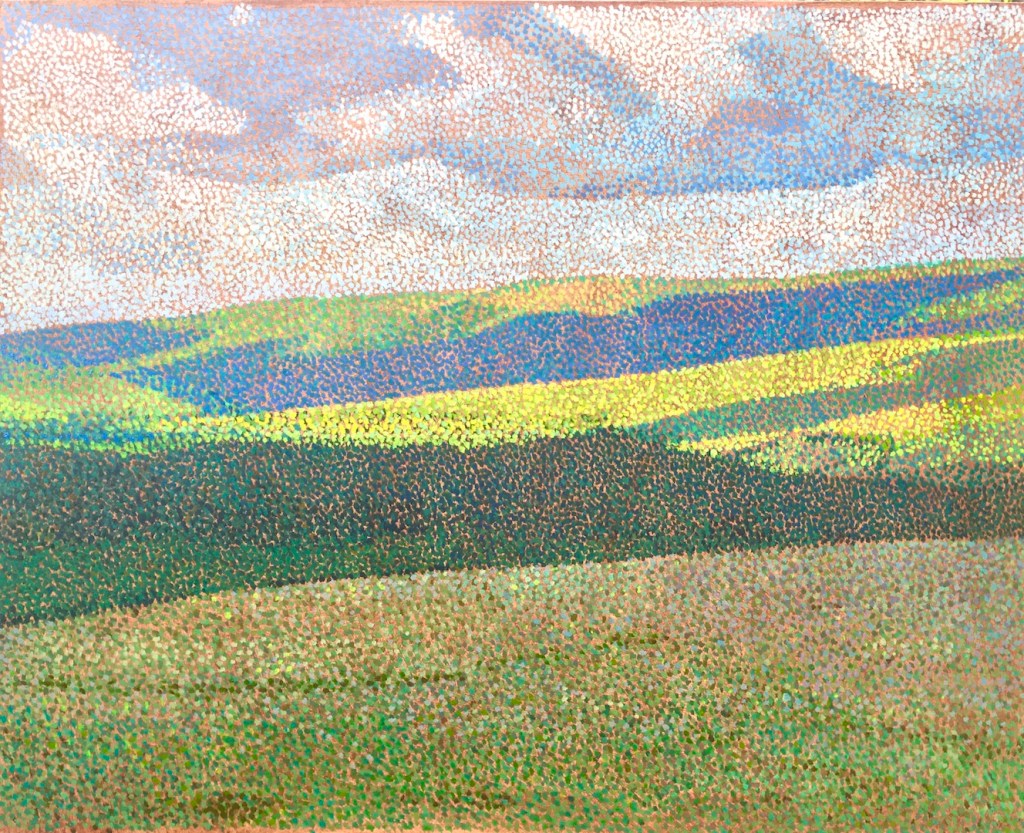

Changing light across dartmoor

Posted on June 17, 2021

Here the change from light to shade, and the kaleidoscopic colours that result across the hills on Dartmoor in typical English weather. I loved painting the blues and deep violets against the ochres and umbers in the shadows. I love colour! That’s why I love painting. This is all painted in a looser style than my pointillist paintings, and I feel more comfortable painting in this way. Its faster, in the sense that I can record my feelings more directly. I sometimes spoke to the landscapes I painted. Sitting in a landscape and thinking about how to render it in paint is a very intimate experience, like meeting a person. Eastern philosophy teaches that we are one with the earth and the stars and our life contains the vastness of space. Spending hours in a landscape painting is like spending hours with a person, talking, laughing. I still feel empathy towards a landscape like I can people, and landscapes or places can become friends who share suffering and joy. Landscapes are not dead things and everything is alive, part of the rhythm of compassion in the universe.

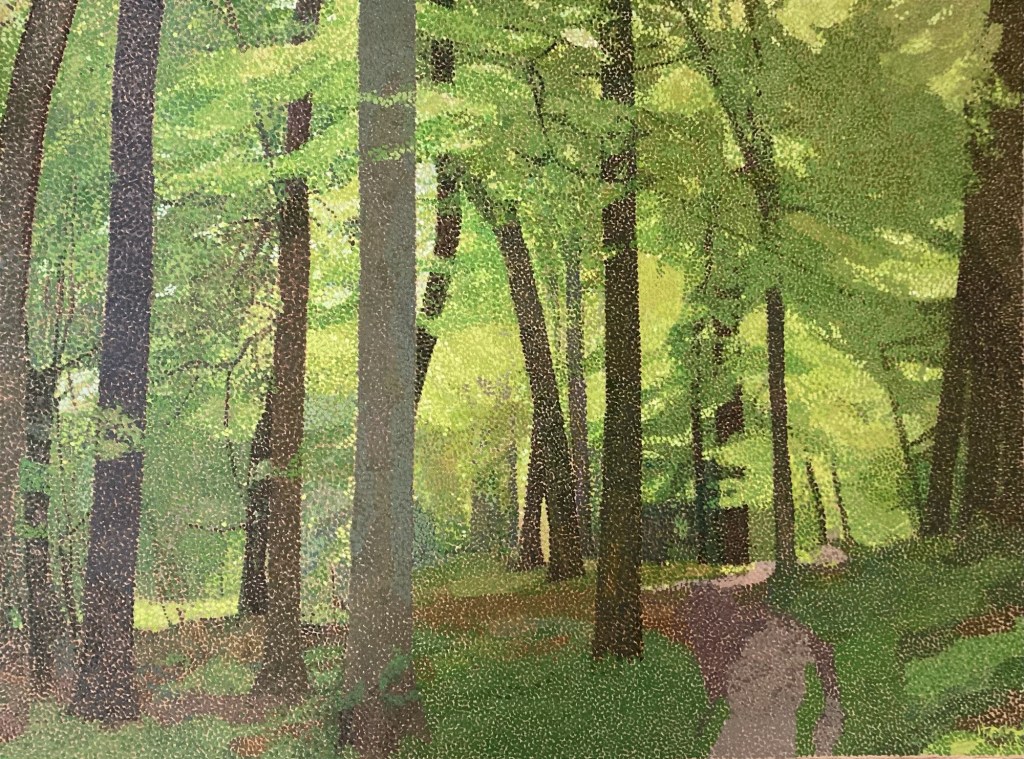

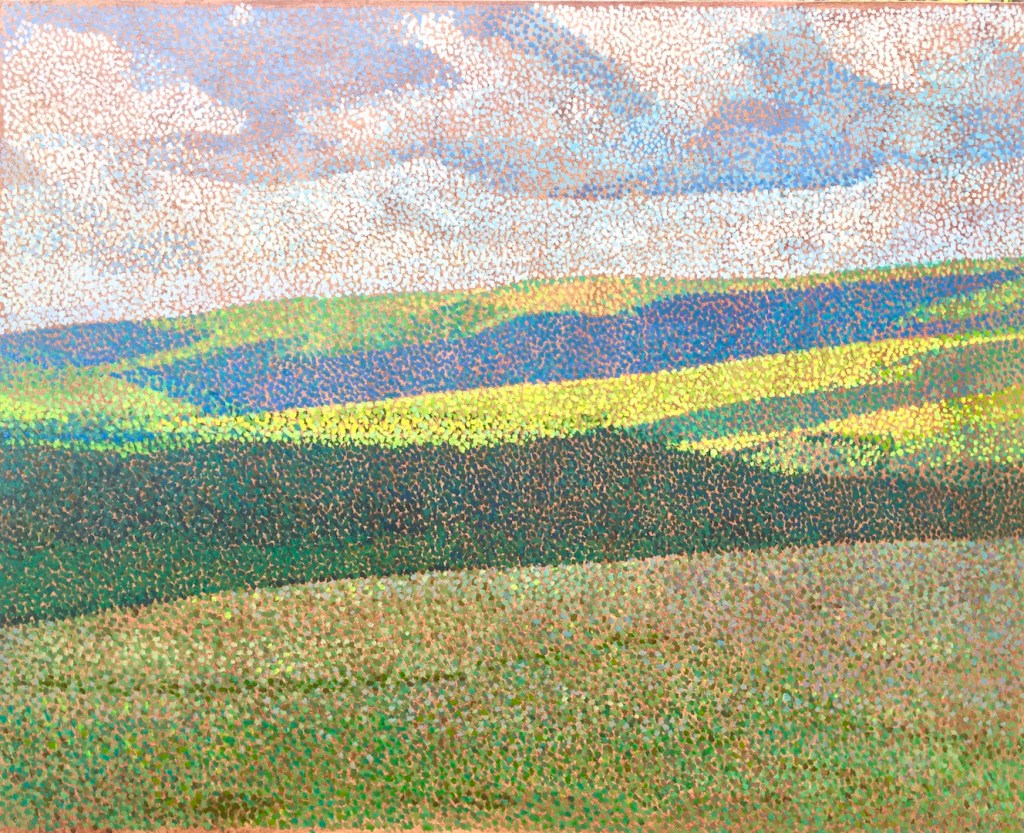

2 styles of landscape painting

Posted on January 30, 2021

Hi there I wrote this for a presentation as part of a show recently, so I thought I would put it up here

I spend a lot of time in the local landscape, especially Dartmoor. The landscape here is always changing and the main subject of my paintings is the depiction of this changing light and weather, and how the landscape can look so beautiful as it reflects this.

So I wanted to introduce you to two different painting styles that I use to try and depict this change. I’m now bringing these two styles, the first focussing on pure colour, and the second which is more gestural and focussed on mark making, together.

This painting shows my so-called pointillist style, using small brushmarks across the painting surface. Pointillism or divisionism was an art movement started by Georges Seurat in the late 19th century. Henri Matisse also used this style early in his career. Painting with dots enables me to keep inventing while painting a landscape. I want to surprise myself with new combinations of colour that I did not anticipate before I started painting. There is a magic in discovering new things in a painting. It felt like pure painting because a spot of colour can work in any number of ways, depending on the other colours surrounding it. It does not change itself, but we perceive it differently as it reflects these other colours.

The dots also display subtle patterns on the surface as they swirl and move about. I like this because this is something I cannot foresee and it is only when the painting is finished that this becomes fully apparent. If I try and plan this or make it happen as I work it ends up looking crude and contrived. So I can discover something I have never seen before which also reflects the idea that nature moves in rhythms and patterns which are not easy to discern. I can see afterwards that I am also a part of this rhythm and this is reflected on the painting surface.

I’m interested in contrasts of light and shade and how they bring out each others qualities.

This next painting is of a view looking east from Haytor on Dartmoor. I was up there recently and the light was very beautiful as the sun set behind me, with everything changing every second. The beauty of the landscape at this time of year and the colours deeply moved me. I hope to convey some of this emotion and would feel that my painting has been a success if someone else feels that too when they see it. I work fairly rapidly and use the brush with more movement, like chinese calligraphy, where the calligrapher lets their emotion show in the movement of the brushmarks. I am always trying to find the simplest and most effective way to express my feelings. Because of my background in sculpture I see these two styles as being akin to two different sculptural disciplines. The pointillism is like carving, where the brushmarks build up to create the forms which crystallize on the surface, like when I am carving stone and the chisel marks grip the form and condense on the stone. The more gestural painting is like working rapidly with clay, moving the paint around on the surface, manipulating it as matter. That’s all painting is – matter pushed around on a flat surface, and there’s a beautiful magic in it for that.

When I am in the landscape, and when I am painting these landscapes I feel happy, I feel the joy of life pulsing through nature and myself. I hope this feeling is communicated and shared through my paintings.

Dartmoor from Haytor, first pass

Posted on January 23, 2021

This is the result of the first go at this painting of beautiful Dartmoor. I will definitely give it a glaze but its nice to have a record of this stage. The important thing is not to overdo it! Like Pisarro I have been trying to ‘escape the dot’, and am relishing a return to a more open painterly style.

I am nature. Dots and landscape painting

Posted on December 16, 2020

The British landscape. Living in south west England means I spend a lot of time in the local landscape, especially on Dartmoor, a beautiful ancient landscape in all seasons, where everything is always changing. The subject of my paintings is this change itself, the depiction of this changing light, and how the landscape can look so different through the seasons, the time of day, and the weather. You can’t paint landscapes in England without painting the weather.

I would like my landscape paintings to be the result of a dialogue between myself and the environment I am in. I feel that any landscape is always alive; changing, growing, and my paintings are the result of a communion I have with the landscape. My life pervades the landscape both spiritually and physically.

I use small brushmarks or dots to build up the image. Let’s say for arguments sake I use a pointillist style. I see each dot as a jewel sparkling with life. Each dot is a thought, like a full stop and a comma, an exclamation mark and a question mark. All around each dot are others sparkling like gems in their interrelations. It’s not me it’s the colours. Dots have the beauty and purity of colours, and while unchanging in themselves, they appear so differently in context, more beautifully expressing their intrinsic qualities. They are the simplest and purest expression of colour as it is, like musical notes. The dots also unintentionally appear to express rhythms and patterns on the painted surface which reflect rhythms and patterns in nature. I do not consciously seek these rhythms but they delight and surprise me in hindsight. It is important that I don’t seek these as I work, and in fact I actively avoid any kind of schema when painting. At all costs I want to avoid mannerisms of style.

These rhythms are not sought but appear to manifest naturally in spite of myself. I am nature as Pollock said, and nature must be present, evidence welling spontaneously in the traces of my actions. There are deeper realities, infinitely profound and immeasurable, that I cannot consciously perceive as I move and act but they are revealed like ghosts in the marks I leave afterwards. Rather a life print than a footprint.

This rhythm is more important to me than colour, being a sculptor, but it gets lost and harder to see the more I work with colour.

Pointillist landscape painting

Posted on October 9, 2020

I’ve been on a journey this year, as has everyone else. In the studio I have started painting landscapes again, and my artistic journey, with many twists and turns and uneven paths, has led me to a series of pointillist landscape paintings. It ties many different strands in my work, but I think the main reason this style suits me for the moment is that dots allow me to respond to the landscape with abstraction. I can begin to invent things which feels good. There is much to say about all of this but for now here is a recent painting. I will show some of the highs and lows from this journey in future posts.

This landscape looks across Dartmoor in the south west of England and shows the viewpoint looking from the shadow cast by a cloud towards hills with shadows on. You can’t paint landscapes in England without painting the weather. Its not all bad, as you can see the suns out over there! Thats a beautiful thing for me and has always been one of the themes of my landscapes. The light is beautiful precisely because of the shade, and there is always change, things never stay the same, there is always hope.